Substance Use Blog Series: Stages of Change and Returns to Use

Sept. 8, 2020

Today’s Substance Use post is going to introduce a way of thinking about change called the Transtheoretical Model, or simply, The Stages of Change. Created by substance use researchers James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente in the 1970s, it has been applied to how people make all sorts of changes in their behaviours, particularly around healthy living.

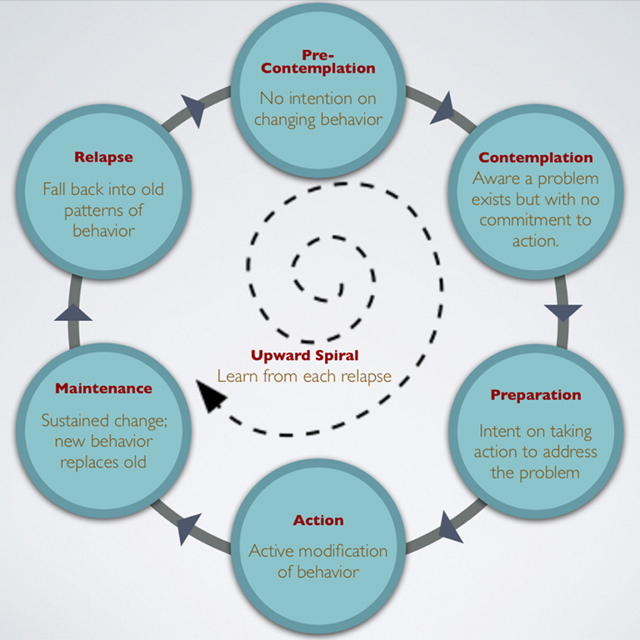

The model breaks down change into 5 main steps. Return to use (aka relapse) is sometimes depicted as a 6th step (like in the video above and in image 1, below) or sometimes as a separate related process (as illustrated in image 3, further down the page). Sometimes the stages are depicted as occurring in a circle, a ladder, or as literal steps (see the images throughout the post).

Image 1. by socialworktech.com click the image to go to the page

The Stages of Change can be a useful framework when we are thinking about making a change. As friends and family members of people who use substances, we may also find the model helpful when considering our expectations and responses to our loved ones.

This post has three parts:

A. A discussion around returning to use while making a change

B. An explanation of each of the 5 Stages of Change

C. Further considerations for family members and loved ones

Keep in mind that there is no right or wrong way to move through the stages of change.

A. Returning to use while making a change

The term ‘relapse’ is very ingrained into the way we discuss change around addiction, so most of the literature (including all the images in this post) still uses it.

However, people are increasingly questioning the helpfulness of the term ‘relapse’ when talking about recovery. This is because the term is often associated with the stigmatizing belief that any return to use is a failure for the person trying to make a change.

The truth is that behavioural change exists on a spectrum.

Thinking in all or nothing terms can increase feelings of shame or defeat when we experience a setback. Because the term ‘relapse’ can carry stigma, some alternate terms are ‘lapse,’ ‘re-cycling,’ or ‘return to use’ – which we will be using for the rest of the post. For further reading on this topic, see substance use researcher William Miller’s discussion of the term ‘relapse’ here.

Each of the three images depicting The Stages of Change in this post give different, important, perspective on return to use.

Image 1 and the video both depict return to use as one of the stages in a cycle of change. This illustrates that, although returning to use is not inevitable, it is normal and often happens several times on recovery journeys. The upward spiral in the middle of image 1 states the important truth that we can “learn from each relapse”.

- Return to use can provide us with important information about our triggers that we may not have been aware of before.

- Return to use might also occur as an experiment after a period of abstinence and/or making other changes in our lives. How such an experiment turns out will give us powerful information about our relationship with substances for when we choose to make a change again.

Image 2. By Philciaccio – click for image details

Image 2 (above) does not include any depiction of return to use. This is an important insight because return to use is not inevitable. Some people who decide to make a change in their substance use, including becoming abstinent, maintain that change. Careful planning and connecting with a strong support network can reduce the chances of returning to use for people whose goal is abstinence.

Image 3 (below) depicts return to use beside the main stages as a separate, related process. This highlights that return to use could happen at any stage. Although it does not always lead us back to the precontemplation stage, it can. As part of the preparation stage, it can be helpful to spend some time considering how we would want to re-engage with the change process after an unplanned return to use.

Image 3. By A8younan – click the image for details

Three more considerations that aren’t captured through the images are:

We do not necessarily go through the steps in order. For example, someone might skip the maintenance stage or go immediately from return to use into action.

The length of time spent in a stage can vary. Some people might spend a long time in the contemplation and preparation stages while others might move quite quickly from contemplation into action.

We may be in different stages of change about different substances. For example, willing to make a change about smoking nicotine but not about marijuana.

As stated before, there is no right or wrong way to move through the stages of change.

B. The Stages of Change explained

Before getting into how the stages apply to substance use, you may find it helpful to think of a change you’ve considered – or tried to implement – in your  own life, and consider how The Stages of Change fit.

own life, and consider how The Stages of Change fit.

For example, I can say that I’m in the pre-contemplative stage about cutting out coffee. I wouldn’t like someone telling me that I should cut out caffeine, but I might move into a contemplative stage if I discovered that it was affecting my health in some way.

Where do you fall in the Stages of Change on any of these behaviours:

- getting more exercise

- meditating regularly

- cutting out unhealthy foods?

The Stages:

- Pre-contemplation – We’re not interested in making a change. Maybe we’re not experiencing any problems ourselves, maybe we’re in denial that there is a problem, or perhaps we’ve grown up in an environment where we’ve never had an opportunity – or it has seemed impossible – to imagine something different.

While in the pre-contemplative stage about reducing or stopping substance use, we may still be open to taking measures to increase our safety. For example, through overdose prevention or harm reduction.

2. Contemplation – We recognize that there are some problems with a behaviour but have mixed feelings about making a change. This is the stage where we are “on the fence”. Perhaps we are experiencing anxiety or uncertainty about what change would look like, or we haven’t decided what we would like to be doing instead of the behaviour we’re engaged in now.

2. Contemplation – We recognize that there are some problems with a behaviour but have mixed feelings about making a change. This is the stage where we are “on the fence”. Perhaps we are experiencing anxiety or uncertainty about what change would look like, or we haven’t decided what we would like to be doing instead of the behaviour we’re engaged in now.

One of the things we might try in this stage is making a small or short-term change as an experiment. What kind of control do we have over our behaviour? If we were going to start making preparations, what would they be? What would have to change in our lives to make a change worthwhile?

- Preparation – We decide to make a change and start preparing by pursuing activities such as: learning about how others have made changes, what kind of supports are available (see our previous posts about substance use services for Delta residents), and connecting with counsellors, health workers, and/or support groups.

- Action – We act on the change we have decided to make. This may mean regularly attending counselling, going into treatment or detox, stopping the use of substances altogether, or reducing the amount of substance we are taking.

- Maintenance – We are making ongoing efforts to continue with, and maintain, the change.

C. Further considerations for loved ones and family members

As discussed in previous posts, having a loved one experiencing problems with substance use can be devastating. The pre-contemplative stage can be particularly upsetting and difficult if the loved one is not noticing or acknowledging the problems that are affecting family members.

The painful reality is, we cannot make anyone change and we cannot force anyone to be more ready for change than they are.

It’s easy to become trapped in thinking that if we are not forcefully pushing for change, we are somehow condoning substance use behaviour.

Accepting the fact that we cannot make change happen for someone else does not mean approval of problematic behaviour.

Thinking about the Stages of Change can help us determine what kind of help our loved one may be open to, and what kind of boundaries we need to set to keep ourselves emotionally (and sometimes physically) safe.

For example, if we spend a bunch of time researching treatment centres and try to present that information to someone in the pre-contemplative stage, we may be hurt and disappointed when they will not sit down and look at the information. They may even express resentment at our efforts.

In contrast, a person in the preparation stage may really appreciate that someone put together information on treatment for them.

Even though someone in the pre-contemplative stage might not be interested in changing their substance use, they might still recognize safety concerns around their use and engage in overdose prevention planning or harm reduction. For suggestions on how to engage a loved one in conversations about overdose prevention, see the Fraser Health “When Words Matter” campaign or review our previous SUS posts on overdose prevention by clicking here or here.

The stages of change can also help us think about what stage of change our whole family may be in.

Although family dynamics may not be the cause of a person’s substance use, the substance use problem began or has continued during certain family patterns of behaviour. Changing family patterns takes effort from family members, and in some cases, can make a difference in reducing substance use. When wanting to support a family member who is using substances problematically, it may help to consider which of the Stages of Change you and any other family members are in around family behavioural patterns.

The Centre for addiction and Mental Health in Toronto has created a short and informative course called Empowering families affected by substance use. More specific information about applying the stages of change to interactions with a family member can be found in that course here.

If you would like to speak with a counsellor about the Stages of Change please contact Deltassist Substance use Services at 604-594-3455 ext. 108.